From spectacular entrances to co-working spaces that exist between the public and private realm, Projects We Love examines the history of the hotel lobby.

First impressions matter. They are the initial moments that set the tone for any future encounter. For most hotel guests, these formative few seconds occur in the lobby – the entrance way to all else that the building and institution might offer them during their stay. As such, the creation of this space – from the furniture and flooring, to the uniforms worn by staff – needs to ensure an enticing and memorable experience. The principal role of the lobby as an area for welcoming guests has remained largely unchanged for centuries. Its primary function has been consistent since the days when travellers arrived at coaching inns, looking for a meal and a bed for the night. Over time, however, lobbies have taken on additional functions, with hoteliers responding to the shifting requirements of guests and seeking to make the most of these liminal spaces – areas that, officially, are private, and yet which have now taken on semi-public functions. From opulent declarations of exclusivity, to places for communal working and socialising, hotel lobbies have tracked changing societal and creative trends throughout the past century.

As a hotel’s main public area – and often a space that is visible from the street outside – the lobby represents the best opportunity for a hotel to communicate its core values to guests and the wider community. The design of a lobby, therefore, typically aims to impress, delight or reassure guests, while offering a unique branded service. “The lobby sets the tone for the overall guest experience,” suggests Adam Weissenberg, global leader of travel, hospitality, and leisure at financial services provider Deloitte. “More than ever, hospitality customers are looking for exceptional experiences and positive surprises the moment they step inside.”

In the early days of the hospitality industry, creating this first impression typically meant relying on scale and ornamentation. The grand hotels built across Europe and America in the late 18th and early 19th centuries targeted the upper classes, and sought to immediately establish their credentials through spectacular lobbies. Many of these establishments are still in operation, and have endeavoured to retain the original character of these spaces. Despite a €400 million four-year refurbishment of the Ritz Paris, which was completed in 2016, few changes were made to the hotel’s elegant red carpeted entrance, while the art deco black and white marble lobby designed in 1929 by Oswald Milne for Claridges in London remains one of the city’s defining interiors.

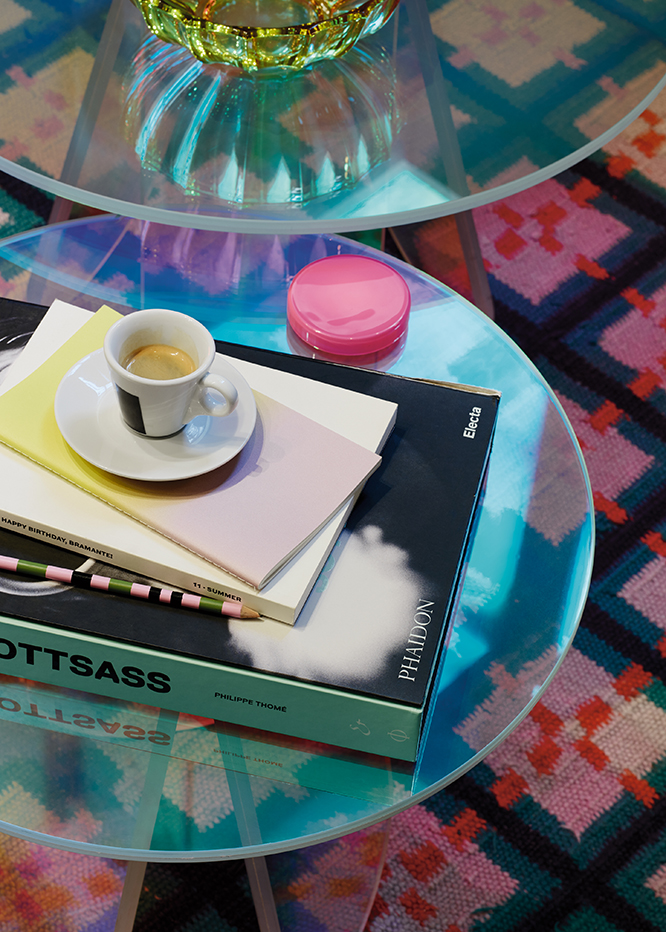

The furniture in the lobby is selected from Italian makers Moroso, Verywood and Glas Italia.

In the mid-20th century, a golden age of hotel design emerged, prompted by the increasing affordability and popularity of air travel, resulting in a surge in hotel construction. Hoteliers seeking to distinguish their accommodation from that of competitors invited renowned architects to oversee the design. For some architects, these commissions offered an opportunity to create a gesamtkunstwerk (a total work of art in which every detail contributes towards a comprehensive vision) as in Danish designer Arne Jacobsen’s SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, which opened in 1960, and the Okura Hotel in Tokyo, which was designed by Yoshiro Taniguchi, Hideo Kosaka, Shiko Manakata and Kenkichi Tomimoto. Both featured lobbies that encapsulated this holistic approach, uniting a grand sense of scale with exquisite detailing and craftsmanship. Jacobsen’s famous Egg chair was developed to provide guests in the lobby with a sense of cocooning privacy, while the Okura Hotel’s entrance featured a central ikebana floral arrangement that was changed monthly.

Souvenirs from the city help to evoke a personal feel.

Towards the end of the 20th century, however, this notion of the gesamtkunstwerk was expanded from single hotels to chains. Ongoing reductions in air fares and the popularity of package tours prompted a boom in leisure travel that saw multinational hospitality firms such as Marriott and Hyatt develop sites around the world. These hotels typically employed a standardised aesthetic, such that guests could feel a sense of familiarity when entering any lobby. A backlash against the homogeneity of these big hotel chains began in the 1980s with the emergence of the first boutique hotels – establishments featuring highly stylised designs intended to emphasise their uniqueness. Hotelier and interior designer Anouska Hempel’s Blakes hotel in London, as well as the Morgans hotel devised by Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell in New York, provided the template for an alternative approach to hospitality focused on eclecticism, locality and individuality. In place of showpiece spaces, lobbies began to take on higher design values and a sense of individuality. It was a change embodied by Schrager and Rubell’s work with the designer Philippe Starck on the Royalton and Paramount Hotels in New York, which featured lobbies intended as social spaces where guests and city residents were encouraged to spend time. Starck’s designs for the interiors of these spaces incorporated dramatic lighting and quirky furniture that resulted in an atmosphere akin to a theatrical stage set, turning the hotel lobby into an exciting and aspirational social destination within the urban realm.

The watercolours above the reception desk are painted by local artist Sandro Fabbri.

“The lobby sets the tone for the overall guest experience.”

This concept of lobby socialising has been further advanced by contemporary hotel brands such as Ace Hotel and W, which invite the public into their lobbies and provide facilities such as communal tables, free Wi-Fi and coffee bars so visitors can spend prolonged periods working or relaxing in these spaces. This response to the trend for mobile working helps the lobby area to function as a lively and profitable venue that exists somewhere between the private and public realms. “The blurring of boundaries between public space and leisure space is already happening,” claims Weissenberg. “It is smart for hotels to meet the lifestyle of the customer, which includes working, playing and living in a single space. The hotel of the future will be an integrator of networks and people to build more personal connections.” It’s an exciting development that will continue to impact the next generation of lobbies.

The success of boutique hotels and the rise of the experience economy have also influenced many of the leading global chains, which have responded by ditching standardised design in favour of more individual interiors. Designer Patricia Urquiola has successfully achieved this with her sleek redesign of the Roman Mate Hotel Giulia on Milan’s Via Silvio Pellico. A 19th-century building that was previously a bank, its historical elements have been combined with strong colours, vintage chic and modern Italian furniture. Urquiola explains, “We had fun mixing panelling from the past with checked wallpaper that looks like maths exercise books.”

Arecent renovation of the Radisson Blu hotel in Amsterdam, as seen on page 29, by Studio Edward van Vliet focused on introducing references to local heritage, while still providing a contemporary aesthetic to match the hotel’s updated amenities. As part of a refurbishment process that saw the lobby transformed into a lively and open multipurpose area, van Vliet specified a custom-made floor tile from BOLON, with an organic repeat pattern that incorporates different hues and tones to help distinguish the various programmatic areas. “It’s important for us to create a strong identity in spaces such as this, so we work a lot with bespoke designs for floors,” says van Vliet. “Choosing BOLON gave us the opportunity to design our own tile shape and to create a floor that perfectly fits our philosophy. It adds that necessary wow-factor to the lobby, which is the main public space and, therefore, a critical perception shaper.”

Terracotta bricks, a typical feature of Milanese architecture, are used on a curved wall in the lobby.

“Mobile working helps the lobby area to function as a lively and profitable venue.”

In fact, the choice of flooring in a hotel’s lobby has always been a good indicator of the sort of experience guests can expect during their stay or visit. Plush carpet evokes classical elegance, while marble suggests sophistication. At the Ace Hotel in London, wooden parquet flooring references the materiality of local buildings, while the robust yet decorative woven tiles at the Radisson Blu Amsterdam combine contemporary style with an essential practicality. As the first thing guests typically come into contact with upon entering a hotel, the lobby floor’s tactile and aesthetic qualities contribute greatly to initial impressions of the space. The surface needs to support the overall design concept and must be robust enough to withstand constant use over years or decades. The most memorable lobbies often feature soaring ceilings or spectacular chandeliers intended to draw the gaze upwards. Sometimes, however, a glance down at the floor can reveal just as much about a hotel’s character.